Blockchain as a Platform for Data Governance 2.0

Last modified: July 14, 2020 • Reading Time: 8 minutes

Background

For many people, blockchain is inextricably linked with currency and finance. Bitcoin popularized the constellation of techniques we now think of as comprising a blockchain but in 2009 when the first Bitcoin block was mined, those techniques were already well understood and had been roving in the wild–in many cases for decades. Like the iPhone, Bitcoin’s success was not rooted in any startling new innovation, but rather the right set of technologies in the right package, set to the right task to provide value at the time.

Blockchain as a technology is new enough to defy precise definition, but as it pertains to possible application as a data governance platform, we’ll point to three primary features shared by systems we think of as a blockchain system:

1. Blockchains are datastores. They answer questions about the current state of some data in a specific data model.

2. Blockchains are modeled as an immutable ledger. A “change” to the database, rather than being a verb, is a noun–a line-item describing both the original state of the database when the client chose to operate on it and the new state as it should be after the operation. As with a familiar, traditional ledger, the actual data being modeled (i.e., how much money is in an account) doesn’t live anywhere on the page–it is simply a “known thing”, a synthetic value knowable at any moment by considering the changes that have been written down, i.e. the initial value of the account and credits and debits over time.

These first two qualities mean that all blockchains are append-only datastores, but the reverse is not necessarily true, owing to the third quality:

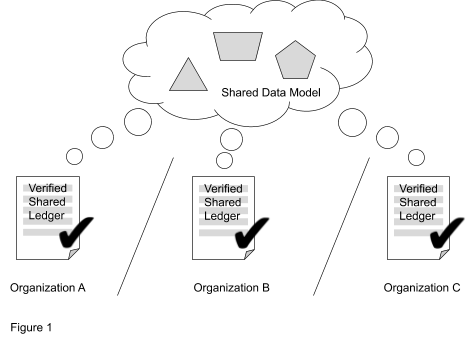

3. Blockchains are distributed across organizational boundaries. There is no one “keeper” of the database and cryptographic techniques are used to ensure that participants in the blockchain cannot “cheat” and update the data in ways the organizational network has deemed undesirable. This requires a consensus algorithm that permits the heterogeneous organizational network to agree on what changes have happened and what their total effect on synthetic data is.

This last feature, the consensus algorithm, originated with Bitcoin as proof of work, an algorithm that asks participants to race to solve mathematical puzzles and compensate them for the busy-work with a token. The notion that this token might one day gain value (which, of course it did) incentivizes the network to provide consensus. But here we circle around to the persistent (and incorrect) notion that Bitcoin is somehow ineluctably bound up with finance and currency: a blockchain platform need not be based on proof of work and need not deal in tokens. Both of these things are features of proof of work and proof of work in not the only possible consensus algorithm.

Bitcoin was concerned with hostile democratic takeovers and adversarial participants. But for blockchain platforms intended for business organizations, where business and service layer agreements already exist and the value of the system itself is the primary shared goal of the network, our concern is more centered around mundane possibilities like a partner reneging on an agreement or a disgruntled employee using data in a way that was not its intent. In this environment, other consensus models such as waiting turns or gathering signatures become possible, which reduce the need for wasteful proof of work, increase network throughput, and require no tokens.

Blockchains are Data Governance Platforms by Default

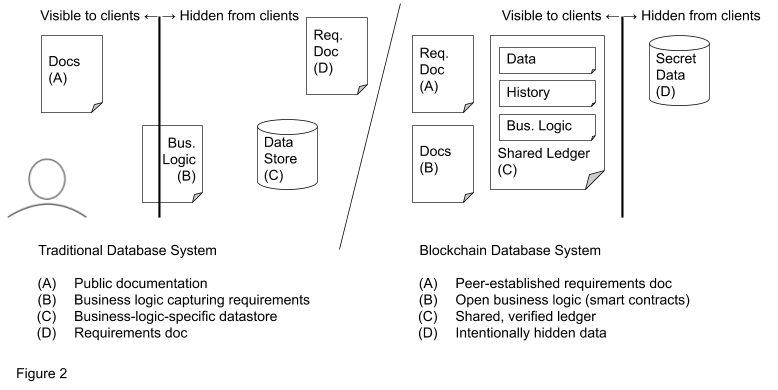

At their core, the blockchain techniques answer a simple question: how do we know our database is consistent? For a traditional database, the answer is “because those who host the database promise not to move the data into an inconsistent state.” For a blockchain database, the answer is instead “because the sequence of events that brought the data into its current state is embedded into the data itself, and any participant may validate that sequence and refuse to engage further with invalid data.”

The blockchain techniques reify the ill-defined nebula of business and technical expectations around the database. The database ceases to be “a datastore with its shifting layers of software, business expectations, and unknowable history” and begins to be a self-contained mathematical object whose complete state, history, and governing expectations can be found in a tidy package, shared amongst multiple stakeholders, operated on independently, and validated at a later time by those with an interest in the validity of the data, rather than in the moment by those writing the data.

All this to say, the blockchain techniques enable what is, at its core, a data governance system.

For our purposes here, we consider data governance as all those processes and systems that ensure high-quality data across organizational units, ensure data security, increase consistency, and manage regulatory risks.

In the remainder of this chapter, we’ll explore some particular blockchain patterns and how they can be applied in data governance situations, then examine what indicators should recommend for or against a blockchain solution.

Blockchain Features for Data Governance

Data Chain of Custody

Because an element of data in a blockchain database contains its own entire history, it’s trivial to tag each step in that history with the identity of the user who triggered its change. Indeed, virtually every blockchain platform includes this capability by default (much to the consternation of those who were assured Bitcoin was untraceable). And because an identity almost universally means a public/private keypair, this chain of custody comes with forgery-resistance and anti-repudiation built in.

Beyond simply knowing who changed what and when, the “chain” part of the blockchain ensures that it’s possible to know what the data looked like when the user changed it, which may provide insight into their state of mind, but also provides the intriguing potential for reconciling simultaneous and contradictory edits. Rather than ordering edits by timestamp alone, we can order them by their view of the data at the time they were applied. This can permit lengthy and complex chains of edits to be performed in parallel, siloed inside different organizations, then reconciled later when the edits become known to all.

Reinterpretation of Events

It’s common to store data that reflects workflow, but workflows often differ across organizational boundaries, causing mismatches in expected guarantees. As an example, let’s imagine a hypothetical lab integrity workflow in a hospital.

At Mercy Hospital, lab specimens can be delivered to the lab in one of two ways. One possibility is for the medical provider to deliver them to the lab by hand, in which case they scan the container as they collect the specimen, then scan a secure locker at the lab as they deposit the specimen. The other option is to deposit the specimen into a secure robot, in which case the provider scans the container as they collect, then scans a secure locker on the robot, and a third scan is performed by the lab tech as they transfer the specimen from the robot to a locker in the lab. In either case, business logic in the hospital’s database system marks the specimen as “ready for analysis”.

The problem arises because flagging the specimen “ready for analysis” collapses multiple paths into a single indistinguishable state. Perhaps the lab needs to send the specimen to a third party lab subject to different regulatory requirements. The “ready for analysis” flag tells the third party lab only that Mercy Hospital is satisfied that its internal lab integrity protocols were followed. Were the data instead made available via a blockchain database, the third party could “replay” events according to its own lab integrity requirements and make its own determination.

Furthermore, using a blockchain database, if Mercy Hospital changes its requirements, for example to add a timebox between the initial collection and specimen deposit, all specimens currently in the system could be reconsidered for compliance. In a traditional database system, specimens that have already been marked “ready for analysis” but no longer meet the latest standards may be erroneously processed.

Smart Contracts

Though they are often intoned with nigh-magical significance, a smart contract is merely a computer program that stakeholders publish into the blockchain database and agree in advance to run. By encoding our business level agreements into a computer program, we enable both a level of explicitness not possible in human language and also the true irrevocability that comes from marrying these agreements to the data validity model of the database itself. Because the contracts are published as data into the database, all observers of the blockchain database can agree when the conditions of the contract are met and what the consequences should be. Bad faith versions of the blockchain that ignore or misapply the contract are interpreted as invalid and rejected by good-faith observers.

As a practical example, consider a leasing system for bays in a shared warehouse. There’s no cost to reserve a bay, but to ensure efficient use of a limited resource, a fine is assessed against those who reserve a bay but then do not scan in goods during the reservation window. Reservations and scans are both automatically published to the blockchain database by trusted systems, and a smart contract is published establishing the conditions of the penalty. Without any further coordination, all stakeholders can use the smart contract to agree on how much each participant owes in fines, and any bad-faith version of the blockchain database that attempts to assign an erroneous fine will be rejected as invalid by good-faith stakeholders.

Source of Truth and Doubt

Standard cryptographic techniques allow blockchain databases to elaborate on information about who wrote a given data element with reliable information about from where the data was retrieved.

For example, a participant in a blockchain might write some data about a financial transaction based on the current value of the Dow Jones. Though the participant themselves is not a trusted authority on the Dow, an existing non-blockchain-based trusted web service can provide a signed data value asserting the value of the Dow with a timestamp. The participant then publishes their transaction along with the signed value. We say a participant acting in this way is functioning as an “oracle”, published trusted data from an outside source to the blockchain. The amount of trust assigned to the particular outside entity can be established by smart contract, and future data entries that reference that entity can inherit the same trust level.

Consider a research data hub organized as a blockchain database formed by multiple research organizations. As research is written into the system, it is assigned a trustworthiness, perhaps based on the impact score of the publication in which the data is released. These scores can be published by any participant onto the blockchain (thus acting as an oracle), but must be signed by one of a set of impact-lookup services established in a smart contract. As reviews of the literature and meta-analyses are published into the system, they may reference existing research upon which they are based.

A smart contract ensures that the trustworthiness of a review or meta-analysis is simply the same as the lowest-trustworthiness source upon which it relies. In this way, aggregate data trustworthiness can be tracked through the system, with all stakeholders agreeing on the trustworthiness of a given meta-analysis.

Data Escrow

Combining cryptographic techniques like secret sharing with smart contracts, we can easily create blockchain-based data escrows, in which data is published in encrypted form with a key that can only be recovered by some critical number of stakeholders. A smart contract establishes the circumstances under which stakeholders should publish their key share, and good-faith stakeholders will only do so when the smart contract is met. Provided there are sufficient good-faith stakeholders to prevent a critical number of bad-faith stakeholders from publishing their key shares, the data will remain safely encrypted until the smart contract is met.

Good Fits for the Blockchain

With these features in mind, a blockchain system might be indicated when all three of the following are true:

- The problem involves a consortium of cooperating organizational units, where the data needs to be moved and operated upon across organizational lines.

- The history of data needs to be tracked and each change tied to its author, along with the capability to “roll back” data records to some previous state.

- At least one additional pattern from the last section is needed.

One example of a good potential problem domain might be a social services program, where multiple departments must cooperate to understand how cases move through the system and where, for regulatory and privacy reasons, data escrow is an important feature. Another example might be a manufacturing pipeline where a complete history of every step of the manufacturing process is required cross-organizationally for quality assurance purposes, sources of truth must be carefully tagged, and smart contracts can be used to carefully gate manufacturing steps that can only move forward if certain controls have been maintained.

Of course, there is an implicit requirement at time of writing that the involved organizations have a high level of technical sophistication in order to deploy and utilize such a blockchain network. But those complexities are quickly improving with blockchain systems that use the same industrial programming languages with which the IT department is already comfortable and flexible blockchain platform operating systems meant to be deployed as infrastructure like any other database system.

Bad Fits for the Blockchain

Despite the exhortations of its salespeople, blockchain databases are not a silver bullet, and they have a set of tradeoffs like any database system. Blockchain databases shine when multiple stakeholders need to work together on a common data landscape across organizational boundaries and in situations where burdens of network governance can be fairly spread over multiple technically competent stakeholders. But a blockchain system should perhaps not be the first choice in the following situations:

1. Latency is paramount. Many blockchain platforms struggle with latency due to the need for establishing consensus. While systems that eschew proof-of-work as a consensus model have improved this situation a great deal, few blockchain platforms can match the latency of modern traditional database systems.

2. Storage is at a premium. Blockchains by their nature store everything that has ever happened to the data. Some platforms provide the ability to establish cliffs beyond which transactions are deleted and their effect accumulated into a compacted snapshot, but this significantly complicates many of the desirable blockchain patterns discussed above.

3. Sensitive data needs to be forgotten. Because blockchain ledgers are immutable, sensitive data can not simply be deleted or overwritten. Some platforms provide the ability to replace data with a “tombstone”, which permits it to be expunged without invalidating the history of the ledger. But in most cases, secondary systems based on more traditional datastores will be required to store sensitive data in order to permit key rotation and other standard security techniques.

4. Network governance could break down. If stakeholders are inconsistently motivated to maintain the health of the network, there’s a lot that a sluggish or stubborn stakeholder could do to cause problems for everyone else. In these situations, proof-of-work based consensus with a token becomes more appealing, since it rewards stakeholders for contributing to the health of the network and naturally resists a sluggish or bad-faith participant, but this scheme comes with its own drawbacks.

5. A single organization controls the data ecosystem. Blockchain databases require an ecosystem of cooperating peers to provide their various guarantees. If a single entity controls the generation, access, and regulation of all data, a blockchain provides limited value. Note however that a single organization could begin using a blockchain database and invite others to then participate at a later time, gaining the value without needing to invest the technical effort in the creation of the system.

Conclusion

Blockchain techniques are uniquely suited to data governance systems. The potential to take the entire history of the data, along with the rules for its correct use, and embed those things into the data itself solves a wide swath of data governance issues. Additionally, because blockchain networks are organized around cooperating peer organizations, they can be a natural fit in situations where data governance requirements are truly a mutually-beneficial and cooperative endeavor between business units, or when the regulatory body that controls how the data is used is separate from the organization producing the data.

As with all technologies, there are tradeoffs that should be carefully considered, but blockchain databases may well have a central place in Data Governance 2.0.

Written by:

Dr. Hampton Smith

Reviewed by:

Allen Hillery